"You're losing," the judge said, with a grin, removing his robe to reveal the western shirt and jeans he wore underneath. "I don't credit the testimony of the kid who says his father did it. The victim now has doubts about his identification, and yeah, he apologized to your guy in the courtroom just now, but that's not enough to grant him habeas corpus relief. Look, maybe Mr. Ross is completely innocent, but to win this hearing, you have to bring me some better evidence. Like Nikki Stuart. Bring me Nikki Stuart. That might be something."

The 14-year-old-looking prosecutor nodded in agreement.

That my completely innocent client Ronald Ross would spend the rest of his life in prison -- beyond the six years he had already been in -- was more than I could accept. Ronald just nodded at me. All he had ever said to me was "I know the Lord brought you to me, Mr. Peters." But even with a borderline IQ, Ronald could divine that the Lord did not seem to be driving this toward the proper outcome.

* * * *

There wasn't much time right then to dwell on Ronald. I left the Oakland courthouse and went to the airport, to catch the redeye to Boston.

Aaron Swartz, brilliant computer programmer, internet freedom activist, and elfin, vulnerable 26-year-old criminal defendant had a hearing the next day. Aaron faced 13 felonies for accessing the MIT computer network "without authorization" and "stealing millions of dollars worth" of academic journals. In fact, Aaron was an authorized user of the MIT network, and the obscure academic journals he downloaded had been created with public money, and are now largely given away for free. But Aaron's prosecutor was trying to build a reputation in "computer crimes," so he had turned this dog of a case, properly resolved with a stern lecture and dismissal after a probationary period, into a front page federal felony. When I urged him to resolve the case on terms that wouldn't destroy Aaron's life, he just shook his head. "Your client will have to plead guilty to all 13 felonies, and the government will insist on a prison sentence."

The hearing went well. The Court ordered an evidentiary hearing on our claims that government searches had been unconstitutional. Afterwards the prosecutor handed me an envelope containing a document he should have turned over months before, but which showed that the prosecutor had been personally involved in the events underlying our claims of an unconstitutional search. It appeared that some of his statements to the Court had not been truthful. After reading the document, I looked up to study the prosecutor's face, but he had already moved haltingly down the hallway steadied by a cane with an ivory handle. I could tell we were making progress for Aaron.

I headed to the airport to get back to San Francisco in time for our firm's Christmas party at Bimbo's night club.

* * * *

December 19-21, 2012 2012 had been a hard year. So I packed it in after a holiday lunch on Wednesday, December 19. I met my daughters in front of Macy's on Union Square and we Christmas shopped, had a hot toddy and I intended to wind down for the holidays.

Later that night thoughts of Ronald Ross in his prison cell kept me from sleeping. I awoke at 5 a.m. with Ronald on my mind. A few hours later I was boosting investigator Keith MacArthur up over a fence surrounding a small housing project in east Oakland, looking for Nikki Stuart. Nikisha (Nikki) Stuart was in the center of the events that had sent Ronald Ross to jail for life. The one time I met her she struck me as one of the hardest, most heartless beings I had ever encountered. Back in 2006 Nikki lived with her mother and several of her children in a West Oakland project called Campbell Village. Her oldest son, Steven Tyrrell Embrey, Jr., was 14. He had gotten into an argument with a man named Renardo Williams, who had accused Steven of hitting Renardo's daughter. Renardo had then hit Steven. That led to a confrontation with Nikki which ended badly, Nikki walking out of Renardo's place saying, "I will have my man come and see you."

The next evening Renardo responded to a knock on his door and found Steven and two men standing on the ground below his front stoop. One of the men asked Steven "Is that the guy?" Steven said it was. The man then confronted Renardo about the prior incident with Steven. Renardo acted anything but contrite, and a few moments later the man withdrew a small .22 pistol and shot Renardo once in the abdomen. Renardo staggered inside and called 911, and the three individuals who had confronted him vanished into the night.

* * * *

Ronald's was not my first case representing an innocent California man serving a life sentence. Before Ronald I represented John J. Tennison.

This isn't really how I make a living. I am a trial lawyer, but I work in a firm. I defend people in white collar criminal cases -- sometimes CEOs, investment bankers, lawyers, even some professional athletes. I have tried patent cases, trade secrets cases and attorney malpractice cases on behalf of large corporations and law firms. I have a nice office and a loyal secretary. I get paid well and can get lunch brought to my desk. I represent the damned, I suppose, only because I fear so deeply being one of them.

A certain type of person regularly asks me why I do this. What is it like, I am asked, to represent someone if you know they are guilty? It sounds flip, and plays easily into the notion that I am a sociopath to answer, truthfully, that representing a guilty person is easy, relatively stress free. It is representing the condemned but innocent which brings with it a private hell.

One day Bruce Tennison approached me. Bruce has worked (and still works) in the parking lot next to my office. It is impossible not to like Bruce. His playful smile can warm a cool San Francisco morning. His nickname for me "Slim," is obviously false, but much appreciated. The warmest part of a San Francisco day is often at around 3 p.m., which is often a slow time in the parking lot. At about that time, Bruce can be found standing in the Sansome Street sunshine, the plastic tip of an unlit Swisher Sweet between his teeth, studying the movements of passing women. "Mmmmm-hmmm," he might say, turning to me. "What you need, Slim?"

Bruce asked me to take a look at his brother's case. Bruce had been told by others that I was a decent lawyer, but he had at first refused to believe it, because there was no way that a decent lawyer would drive such a shitty car. But he asked me anyway. And my heart sank. Bruce's brother was serving life for murder. What I could I do for Bruce's brother? How could I say no? We went to the corner bar, The Ship, for an apricot brandy and Bruce handed me a folder containing a newspaper article, the transcript of taped witness interview, and a Ninth Circuit decision ruling that John J. Tennison was entitled to a hearing on his habeas corpus claim.

* * * *

Renardo Williams had plainly been shot because he had hit Steven Embrey, Jr. and then argued with Nikki Stuart. Steven's father, and the father of Nikki's baby, Steven Tyrrell Embrey Sr. ("Senior") was known to Oakland police as a violent person. He is presently in custody for the unprovoked shooting of a different person, followed by a high speed car chase and a shoot-out with police. Yet, despite the obvious connection of Renardo's shooting to a man motivated to stand up for Steven and Nikki, Senior was never investigated by the Oakland police in connection with the shooting of Renardo Williams. He was never questioned. His photo was never placed in a photo spread. He was never put in a lineup.

Instead, the OPD somehow became suspicious of Ronald Ross. Ronald's only connection to these events was that once, ten years earlier, his mother had lived in a neighboring apartment to the apartment occupied by Nikki's mother. In addition, Renardo's live-in girlfriend Melinda Ross, who he was later convicted of savagely beating up, was the daughter of someone named Ronald Ross. But that was a different Ronald Ross, and Melinda had never met her father. This Ronald Ross had no connection to Melinda, Renardo, Steven or Senior, other than that he still lived in the neighborhood. And there was no evidence that Ronald had ever in his life done anything violent or owned a gun. He was a gentle soul who slept on his mother's couch. Ronald enjoyed watching basketball on TV, smoking weed, and maybe sometimes crack cocaine.

While Renardo lay on a morphine drip in the hospital, a bullet lodged in his side, OPD asked if he could pick the shooter out of an array of 6 photos. Never mind that Renardo had consumed a hit of ecstasy, three quarts of Miller High Life and two blunts before being shot. Based on all well-accepted psychological research regarding eyewitness identifications, Renardo's identification of a photo was likely worthless. But Sergeant Lovell showed him an array of photos, with Ronald Ross's photo as #4. Renardo picked Ronald's photo. At trial he testified that the man in court (Ronald) was the shooter.

The People also called Steven Embrey as a trial witness. Steven first testified that he could not recall who the other men with him were and then testified that they wore hoods and he did not know who they were. After a recess in the proceedings, during which the Judge shared his incredulity with Steven, and also during which Nikki had the chance to talk sternly to her 14 year old son about whose interests lay where, Steven returned to the stand and pointed to Ronald Ross, testifying that he did the shooting. There was no explanation as to why Ronald would have done this, whether he even knew Steven, or had even spoken to Nikki in 10 years. No physical evidence connected Ronald to the crime. Ronald had an alibi. He was at his mother's house watching a basketball game on tv with friends when Renardo got shot. Several friends and his mom corroborated his alibi. Ronald testified the game he had been watching was an NBA playoff game. But his lawyer hadn't done his homework. The prosecutor had. He confronted Ronald with the fact that the NBA playoffs didn't begin for another week after the date of the shooting. Ronald couldn't explain this discrepancy. And while it was really beside the point which basketball game Ronald had been watching while Renardo got shot, it damaged his credibility not to have testified accurately about it. So Ronald was convicted by the jury, and sentenced to 25 years to life in California prison. He was at Solano when the Innocence Project first called me about his case, and in San Quentin when I first went to see him.

San Quentin is as brutal and horrible a prison as I have ever been to, the juxtaposition of its idyllic setting on the shores of San Francisco Bay offsetting the cruel, nearly medieval conditions inside the peeling walls, also containing California's well-populated death row. Going to San Quentin always makes me unspeakably depressed. Prisons in general terrify me. I live in fear of incarceration.

God only knows then why I gravitated to this line of work.

* * * *

Every time I visit a prison I fear not being able to leave. That feeling was particularly acute when I went to see John Tennison in Mule Creek prison, located in the Sierra foothills in the town of Ione, California, back in early 2000. Maybe it was the low-slung antiseptic feeling of the place. By then I knew enough about John's case to know that he was innocent, and also that his present habeas case had no chance of setting him free. I had come to meet him and tell him that his habeas claims had to be re-filed in state court in order for him to have a real chance at winning. It meant at least another year in jail before even having his next day in court. John took the news well. "I can do the time standing on my head," he explained, "but I worry about my mom. She can't take visiting me up here many more times." So going back to state court and burning a year to procedurally "perfect" his claim was settled.

"But why do you care?" John asked. "Why are you up here to see me and get involved in my case?" Good question.

"Because I can," I answered limply. "Because as a lawyer I get to. I get to fight for people who have gotten screwed." John tossed me the glance of a guy who had been in prison since he was 17 and knew how to call bullshit while keeping his mouth shut.

John was in jail for the gang-related shotgun shooting death of Roderick Shannon. At trial the People argued that John had held Roderick, late one night in a supermarket parking lot following a car chase, while Antoine Goff had shot Roderick with a shotgun. I knew John was innocent because it turned out the police had taken a detailed, tape-recorded confession of another man, Lovinsky Ricard, who had admitted shooting Roderick, and explained how the chase and the killing had gone down. Ricard's confession about the circuitous geography of the chase made sense, while the People's theory at trial of the chase made no sense and was geographically impossible. But the cops had simply tossed the cassette containing Ricard's confession into a drawer, and never shared it with John's lawyers until much later. When the tape finally came to light, the judge brushed it aside as inadmissible and sentenced John to 25-life.

It had taken years for us to get John Tennison out of jail, but we had done it. Got Antoine Goff out too. I remember Bruce handing his cell phone to John to talk to me as the two of them and their mother were driving away from Mule Creek the Friday of Labor Day weekend in 2003, "John?" I said "John?" Nothing. Then I heard John's gentle, alto voice asking his brother "How do you use this thing?" Fourteen years earlier, when John had last been free, no one used a cell phone.

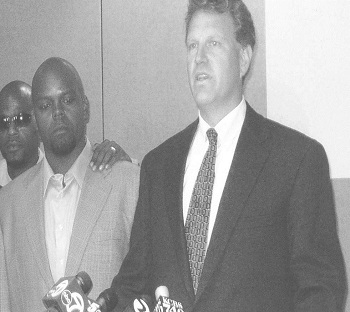

I have a photo on the wall over my desk, taken just a few days later. I am speaking at a press conference about John, who stands behind me wearing a new sports jacket, with Bruce next to him, scowling uncharacteristically, his arm draped around his brother's shoulder. John settled his lawsuit against the police and the city of San Francisco for millions. He lives in a stucco house with a swimming pool. His mom lived there with him until she died recently of cancer.

* * * *

We can win Aaron's case. What he did wasn't a crime in the first place. But Aaron is brilliant, shy, and teeny, not a person who can tolerate much risk of a lengthy federal prison sentence. And it is a trivial case. So I spoke to the prosecutor again.

"We need to find a way to make this case go away. You can claim victory, but this case can't destroy Aaron's life."

"He must plead guilty to all 13 felonies in the indictment and we will insist on having the right to argue at sentencing for jail time. If there is a trial we will seek a sentence of 7-8 years in federal prison, and we have a pro-government judge who is a tough sentencer. Going forward, any offers will only get worse, from your perspective." Saying "fuck you," or "go fuck yourself you self-righteous asshole," I have found rarely improves my negotiating position with a federal prosecutor, so I kept quiet, put down the phone, and set to work on winning Aaron's case.

* * * *

When the Innocence Project brought us Ronald's case it was easy to figure out he was innocent. He had nothing to do with the people or the incident. It seemed obvious that Steven's father, Senior, was the most likely suspect. So we hired Keith MacArthur to see if we could track down Steven, or perhaps even Senior, and help Ronald out.

I have come to love Keith MacArthur. I have heard black people describe Keith as white and white people say he is black. Keith moves seamlessly among worlds. He plays bass guitar and makes the best cappuccino I have ever had. He is a criminal investigator and a musician; a creative man and a tactical thinker; a student of human nature and a determined guy. Keith tracked down Steven and got him to talk.

Steven was a different witness than Renardo. He wasn't making an eyewitness identification based on his memory while looking at mug shots. He actually knew who shot Renardo. The shooter talked to Steven before pulling the trigger, and asked for confirmation that Renardo was the guy. The problem was that Steven had a reason to protect his mother and his father and also, Steven has a substantial cognitive disability. Whether he is retarded or on the spectrum of autism or developmentally disabled or whatever, it is hard for Steven to relate information that seems truthful. This is because much of what Steven reports is just fantasy. That is just how he rolls.

But Steven is capable of telling the truth, and he decided to do so with us. It was his dad, Senior, who shot Renardo. Nikki had told Senior about Renardo's hitting Steven, and Senior had come over to Renardo's place with Steven and another friend to confront him. When Renardo talked back to Senior, he got shot. Simple. Keith always had a succinct way of describing Renardo: "shootable." When I later met Renardo I learned how true that was. On that occasion Keith and I showed Renardo a photo of Senior, which he looked at for a long time. He had never been shown a photo of Senior before, and he told us that this guy looks a lot like the guy who shot him and made him doubt his identification of Ronald. He also said that he had always understood the guy he identified in court was Steven's father, and was surprised to learn that he wasn't, and that this fellow in the photo that looked just like the shooter was.

So based on Steven's recantation of his trial testimony, Renardo's doubts about his trial testimony and some other good evidence we dug up, we got a hearing for Ronald Ross and presented Steven's testimony and Renardo's testimony. Both witnesses apologized to Ronald right there in court. And right after Renardo's apology the judge in the western shirt had shared with me that I was "losing."

* * * *

After I boosted him over the fence at Nikki's dumpy dwelling place, Keith let me in through the gate. We banged on her door. The neighbors came out, as they had on several prior occasions, and asked if we were cops. No answer from inside Nikki's. We looked in through the windows and saw only a mess. No Nikki.

This was the Thursday after I had decided I would stop working for the year and Keith and I drove back towards downtown Oakland, agreeing that facing the holidays knowing innocent, gentle Ronald would spend the rest of his life in San Quentin wasn't an option.

"What if we go see Senior?" Keith asked.

"He'll never speak to us"

"We'll never be okay if we don't try."

"Word. Where is he?'

"Napa."

"Not too bad. An hour away. Let's go tomorrow."

Actually Keith was wrong. Senior was in Atascadero at a state prison hospital, four hours south. He had been declared incompetent to stand trial and sent to Atascadero to recuperate. He might be a vegetable. He had twice before refused to discuss Ronald's case or Renardo's shooting with Keith. But we had to go.

That is how I found myself banging at Keith's door on December 21 at 5:55 a.m., the second full day of my holiday break from work. Keith stepped out with two cappuccinos and we headed south. My car, a fairly new Audi convertible, started shaking just outside Morgan Hill. Engine light flashing. Fuck it. We could just go home. We pulled off and got a tow truck whose driver dropped us at an Enterprise rental place which was just opening. A white Hyundai would take us further south to Atascadero. A great breakfast somewhere off 101, including fresh biscuits and homemade sausages was the first decent omen.

Atascadero is a prison with the word "Hospital" placed on the door. Inmates are "patients." In a visiting room Steven Tyrrell Embrey Senior, dressed in orange, shuffled slowly through the door. He hadn't had a visitor since getting there and wasn't sure who we were or why we were there. We asked him about his recovery and he said he was getting better. We offered a coke and some vending machine food, but he had to settle for a Sprite (no caffeinated beverages at the hospital) and some sour cream and onion potato chips. He ate them slowly and drank his Sprite in teeny sips. It looked as if chewing the chips was making his gums bleed. Senior seemed to be rational, able to communicate and willing at least to eat snacks with us. So I turned to the reason for our visit.

"We represent this guy Ronald Ross who is doing 25-life for a shooting in Campbell Village back in 2006. A man named Renardo Williams got shot. We think Ronald is innocent. Do you know anything about that?"

"He didn't have nothin to do with it." Senior said slowly, with a trace of indignation. "He wasn't even there. I don't even know the dude."

"Do you remember what happened?"

"Sure. Me and my friend Dennis were driving down 10th Street by Campbell Village and we saw Little Steve. He was musty -- stinky, wet, so he got in the car and I took him over to his mom's place. I was gonna whup him, but Nikki said don't whup him, some guy already beat him with a stick. I said, where's the dude at? Then me and Little Steve and Dennis walked over there. Little Steve showed us the house and knocked on the door. When the dude answered, Little Steve said that's the guy. I asked him "Did you hit my son?" The guy said that yes he did, and he'd do it again. I was taking off my shirt to fight the guy when Dennis said "I got this," pulled out a .22 pistol and shot the guy. Then we took off."

It was stunning. Here was the story. Told so casually, but so consistent (except for who pulled the trigger) with everything we knew, including what Steven had testified to in court. Ronald was innocent and we could prove it. I tried not to act excited. I could see Keith was also trying to act nonchalant. We had somehow been able to bring a small digital tape recorder into the facility and we asked Senior if he would repeat what he had just said on tape. He did. We bought him a Butterfinger, thanked him and left, with the digital recording in Keith's pocket.

* * * *

December 26, 2012-January, 2013

The day after Christmas we filed a transcript of the tape, an affidavit about the meeting with Senior, and a supporting brief, with the Court. I sent an email to the DA (the real, elected one, not the 14-year-old) pleading for her to recognize Ronald's innocence and join us in seeking his release.

At a hearing on January 3, the prosecutor (the 14-year-old) confided that she hadn't listened to the tape, read the transcript, or even read our brief. She told us she expected the People to take the position that Senior was incompetent to give testimony, and to persist in opposing Ronald's petition for habeas corpus.

The Judge had read the brief and the transcript. He set another hearing for February 1, at which Senior would be brought to court to testify, likely to take the fifth and refuse to testify. In the meantime we asked to meet with the elected DA to plead for Ronald's release. She met with us, but showed up appearing to know nothing about the case.

* * * *

On January 11 Aaron Swartz committed suicide by hanging himself with a belt in his Brooklyn apartment. News media went on a frenzy about his case, speculating about the relationship between his federal prosecution and his suicide. I attended Aaron's funeral outside Chicago and delivered a eulogy. Demonstrators from the Westboro Baptist Church showed up to decry Aaron as a hacker criminal, but Anonymous hacked their web site and showed up in force on the streets outside the synagogue to shut them up. The Westboro people went home. I was impressed by how effective these shadowy tech activists operated as vigilantes. Later, I felt the cold travel up from the ground, through my shoes and into my legs as Aaron's ashen parents and sobbing girlfriend shoveled frozen earth onto his casket.

* * * *

February 2013

Senior took the fifth as expected. The Judge admitted the tape recording of his statement in evidence, over the prosecutor's objection. The judge recessed the case for two weeks to hear closing argument and make a decision. He seemed inclined to rule against us.

* * * *

Two days before the final hearing, I got a call from the elected Alameda County District Attorney. "We no longer have faith in this conviction and will not oppose Mr. Ross's petition for habeas corpus. We will join you on Friday in seeking Mr. Ross's release." I could barely speak. We went to Court Friday jubilant. TV cameras were in the hallway. The judge was furious. Speaking to us in the privacy of his chambers, outside the hearing of a packed courtroom, he lectured. "I am not releasing this man based on an oral application and a backroom deal. The People need to file an amended answer to the habeas petition and we will take it from there. I will put this over a week." I couldn't believe Ronald would have to spend another week in prison. Leaving the judge's chambers and returning to Ronald, sitting in the expectant courtroom, I wiped sweat from my forehead and flicked it onto the tiled floor.

Ronald seemed cool with it. "I love you, man," he said.

A week later Ronald walked out of Santa Rita wearing new pants and a handsome black shirt our paralegal Rhonda had picked up at Macy's, insisting she pay for it out of her own pocket. Keith was at his side. Ronald appeared on tv that night, dignified and proud. He went home to his mom's and ate oysters.

* * * *

March 2013

Three weeks later I attended the Innocence Project annual dinner with Ronald, John Tennison and Antoine Goff. MC Hammer came by to say hello. "Elliot got me off once too," Hammer said with a grin. I had recently helped get him out of a very minor "dwb" (driving while black) scrape. The pictures taken that night of Hammer, Ronald, John, and Antoine are priceless.

* * * *

I saw the judge at a lawyers' event, the type I try hard to avoid. He asked what me and my "entourage" (three other lawyers from my firm worked on Ronald's case, along with two from the Innocence Project) thought of him when we realized he wore a western shirt, no tie, and jeans under his judicial robe.

I called Ronald to tell him that story, and he just laughed. "That judge never liked you, Elliot. But I love you, man."

* * * *

The next Saturday Ronald came with me to my son's high school baseball game. We sat in the sun-drenched bleachers at Oakland Tech and ate fried chicken sandwiches from Bakesale Betty's. Ronald stood and cheered when my boy got a hit.